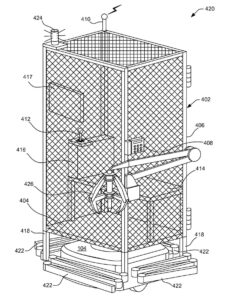

The wage cage is a meme inspired by a patent Amazon filed a few years back. The patent supposedly has something to do with worker safety in warehouses or something, but it’s literally a cage for employees – just look at the pictures.

The wage cage is a meme inspired by a patent Amazon filed a few years back. The patent supposedly has something to do with worker safety in warehouses or something, but it’s literally a cage for employees – just look at the pictures.

And while the working conditions at Amazon are particularly memeable, the current economy is squeezing employees everywhere.

When I started work, I remember complaining how easy the boomer generation had it: They left school, bought a house (that would increase in value much faster than inflation) with a standard 9-5 weekday job, could afford to raise a family, and were able to retire at 65 or sooner with a decent pension.

I thought it was unfair how much harder millennials had it in the post-2008 economy. But I had no idea how much worse it was going to get for the next generation – the ones entering employment in the post-Covid economy.

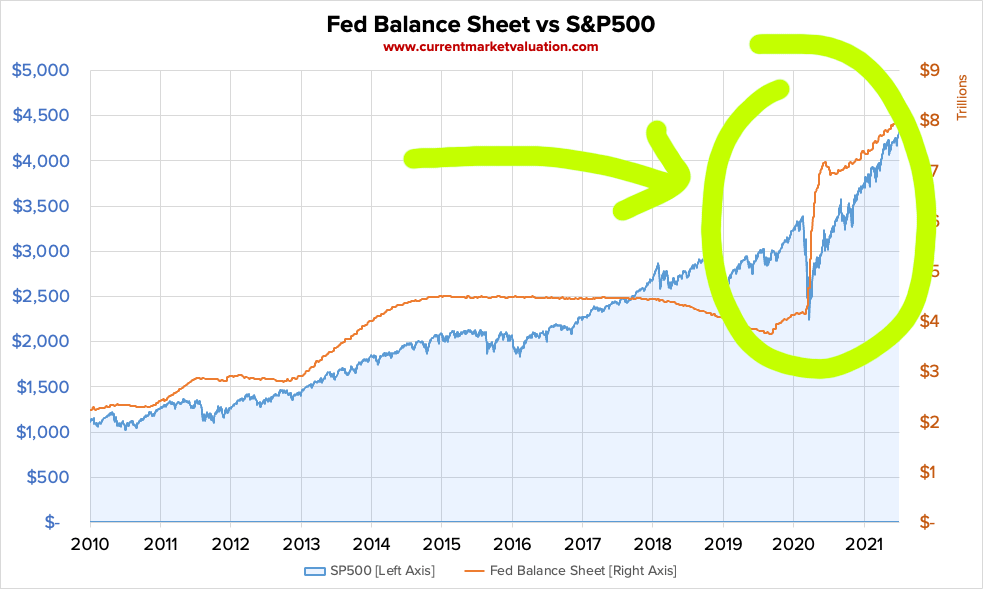

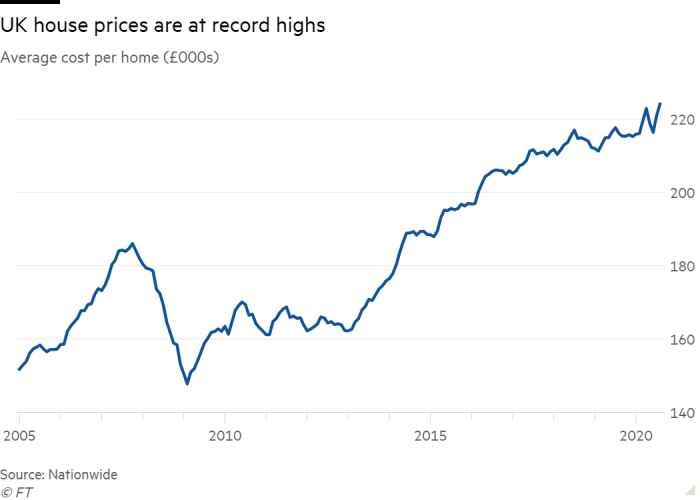

House prices are continuing to rise. All major stock indices are at or near all time highs. Asset prices are booming pretty much across the board – but wages aren’t.

It gets worse, though. Not only is it becoming increasingly difficult to build assets and wealth, everyday items are increasing in price too. Inflation expectations keep getting adjusted upwards in the wake of unprecedented money printing and borrowing. Inflation is expected to be around 4% or 5% a year for the next few years, with food prices expected to increase even faster. We’re potentially looking at a scenario with compounding inflation and slow economic growth for years to come.

You can call it a conspiracy theory if you like, but the World Economic Forum’s vision for life in 2030, where you “own nothing, have no privacy and life has never been better”, is looking increasingly prescient – except for the part about life never having been better.

A term I’m increasingly hearing to describe this nightmare economy is ‘neofeudalism’. In the original feudal economy, a small handful of lords owned all the land and many peasants had no option but to serve them as serfs.

In the neofeudal post-Covid economy, there is an ever-shrinking handful of megacorporations (the lords) and an ever-growing class of people who are entirely dependent on them (the serfs). Many small- and medium-sized businesses have been forced to close for good, but big companies are achieving all time high stock market valuations. And while much of these record-high valuations is just inflation, this inflation does not translate to wage increases. Relative to the employee’s labour, asset prices, food, and other essentials become increasingly expensive, which makes the serf increasingly dependent on the lord.

Given this economy, the wage cage has taken on a broader metaphorical meaning. It’s not just a physical cage, but a societal cage – and one that’s getting increasingly difficult to escape from. I’m sorry for painting such a depressing picture, but the trajectory really isn’t good.

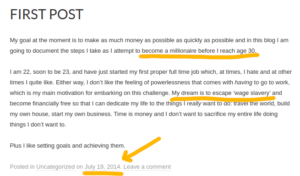

It is still possible to escape the wage cage, though. I recently rediscovered a blog I started 7 years ago where I outlined my plan to escape the wage cage before age 30. I stuck to that plan (with a few minor changes) and it worked out. A lot of what follows is the same basic financial literacy I was writing about back then, with some of my own experiences from along the way mixed in as well.

It is still possible to escape the wage cage, though. I recently rediscovered a blog I started 7 years ago where I outlined my plan to escape the wage cage before age 30. I stuck to that plan (with a few minor changes) and it worked out. A lot of what follows is the same basic financial literacy I was writing about back then, with some of my own experiences from along the way mixed in as well.

Wealth vs. wages

This is such a basic point, but how much money you have and how much money you make are not the same thing.

I’m sorry if this is completely obvious, but this was never explicitly pointed out to me. It’s normal for people to equate these two things – to think that rich people are the ones who have the good jobs and that the only way to make more money is to get a better job or a promotion. It’s also normal for people to spend the entirety of their paycheck (and maybe put a small % away for a pension) and increase their lifestyle as their income increases. But if you read any personal finance book, the first thing it will say is don’t do this.

Saving money and living below your means sounds really boring. But it’s not about being cautious and saving money for a rainy day. Instead, it’s about pulling together the initial capital needed to escape the wage cage.

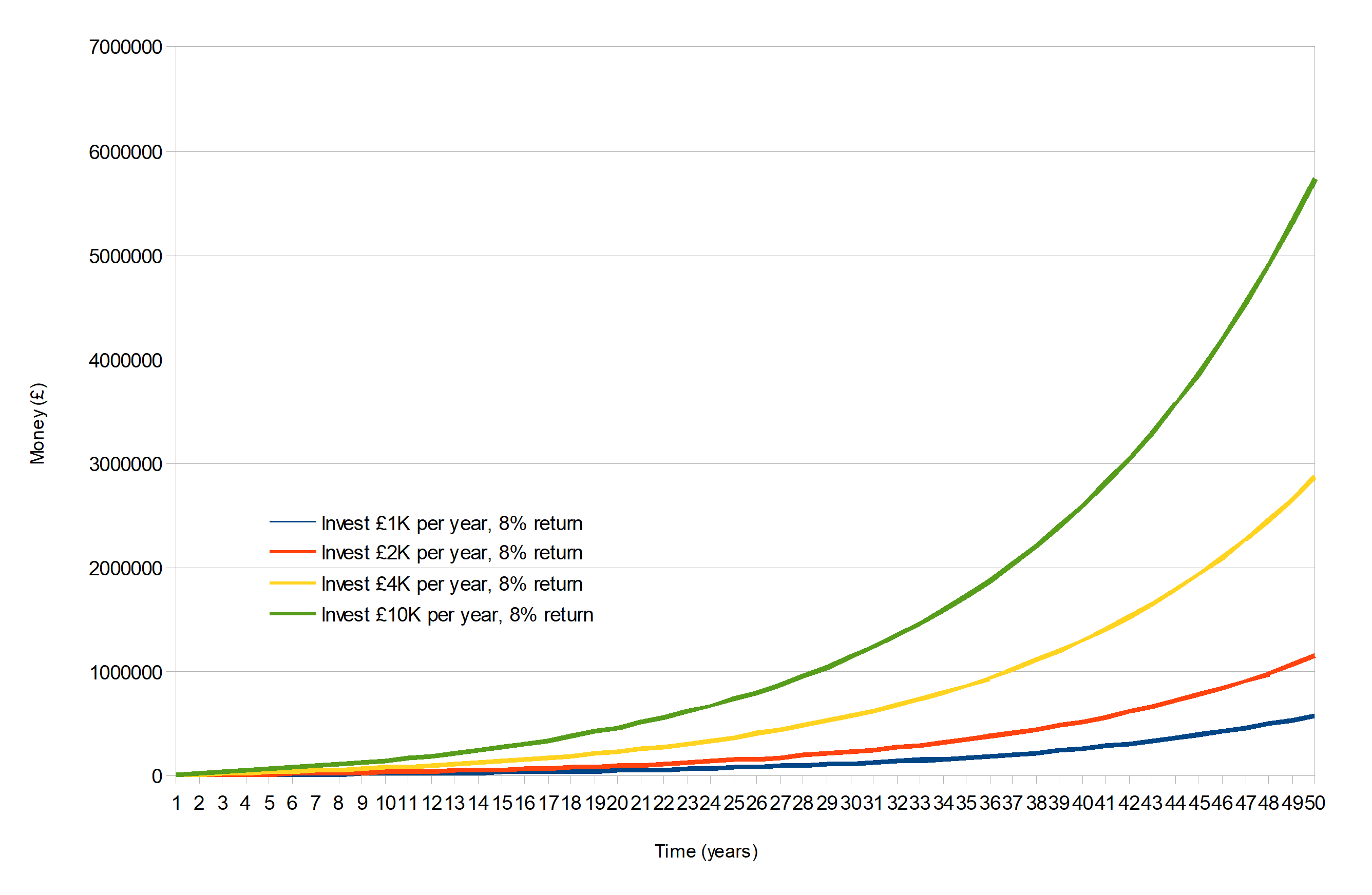

If you’re not familiar with compound interest, it’s really important to understand. I wrote a post on it a while back, so I won’t go over it again here. The chart below gives you the basic idea, though: Anyone can become a millionaire by putting away a few thousand dollars per year and investing in index funds.

I know compound interest is generic boomer advice. And don’t worry, there is more to this plan than to just grind away at an office job for 30 years scrimping and saving. But you really do have to get compound interest into your head.

You have to understand compound interest. It is the measure by which you escape the wage cage or don’t. The steeper that wealth curve is, the sooner you will reach escape velocity: A situation where you are earning more money in interest than you spend in outgoings.

The economic situation described above makes it increasingly difficult to get the ball rolling, though – that’s why it’s so important to start young. This is partly because young people have more time for wealth to compound, but the biggest reason is that when you’re young you can get away with living with your parents or in some dirt-cheap houseshare. Rent is by far your biggest outgoing and so by eliminating it you can easily put away $10k+ per year even on a basic salary (seriously). It’s much easier to save money and take risks when you’re young.

The basic point here is to think of money as a tool you use, rather than something that is just given to you in exchange for your time. All jobs basically pay the same anyway: $70k might sound like twice as much as $35k, but after taxes and so on there’s basically no difference in lifestyle. Don’t focus on trying to sell your time to your employer for more money. Instead, focus on building wealth and assets.

Income streams

But saving money takes a lot of time in the wage cage. Instead, the quickest way to build assets and become more financially independent is to start a business or some kind of income stream outside of your regular job.

When you hear people talking like this – talking about income streams, passive income, starting your own business, etc. – you probably think of scam YouTube adverts and people selling get rich quick programs.

That was definitely my impression for a long time. I thought making money for yourself or starting your own business was some unrealistic pipe dream that other people did, but not me. I thought being realistic and growing up meant accepting the inevitability of the wage cage. Perhaps if I saved and followed the compound interest advice above, I could retire slightly younger than average at age 50 or something. That was the best realistic scenario.

It was only when I actually tried to do my own thing – way later than I should have, at around age 23 or so – that I realised you really can make money for yourself. It’s not some unrealistic fantasy.

In my case, I’d picked up the basics of web design and SEO from the jobs I’d worked. But these skills (at least to the level I’m at) really aren’t that complicated to learn – I’ll probably write another post on building a WordPress site with WooCommerce at some point. Anyway, the first sites I made were on health supplements and home accessories. Even though neither is still running, I learned so much from making them. Obviously there is the practical stuff, but the biggest lesson I learned was that I really could make money for myself. I still remember how shocked I was when I sold my first product. I realised that if I could sell one thing, I just had to scale up and sell more.

This story is specific to my own experience, of course. But the general point is, again, that you really can make money for yourself.

I don’t know what your specific skills are. Not everyone likes writing and building websites like I do. If that’s not your thing, don’t do it. But if you do have a skill or an interest – something you’re good at that other people need – you can build a business out of it.

Tradespeople understand this much better than office workers. A huge percentage of tradespeople start off as apprentices, work a few years as an employee and hone their skills, then leave to become self-employed and set up their own firms. It’s a standard trajectory within the trades, and those who follow it typically make far more money than people who try to climb the corporate career ladder. A lot of enterprising tradespeople also use their skills to become property developers on the side.

The point is: You can capture the value of your skills much more effectively by creating income streams from them.

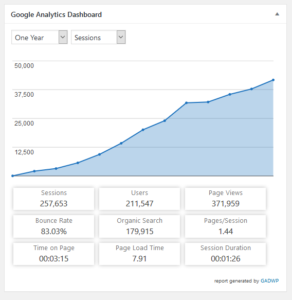

I’d say my work with philosophy is a good example of this. On the face of it, philosophy is a completely useless skill for making money. I love philosophy but it’s so useless that even I had no hope of making money from it. I just put my course notes online back when I was teaching in college because I thought students might find them useful.

Now, though, it makes me a decent income – and that’s not even why I created it. It was just a fun hobby that somehow became a valuable asset. If I can build an income stream from philosophy, you can certainly create income streams from welding, marketing, fishing, or whatever skill or hobby you have.

Interest rates, borrowing, leverage

The conventional boomer wisdom on personal finance is to avoid debt at all costs. This is generally speaking good advice for people trapped in the wage cage. If you max out your credit cards to buy new clothes and furniture, have a car on finance, and take out loans to tide you over until payday, you are stealing from your future self. You are committing yourself to future time in the wage cage in order to pay for stuff in the present. This is bad.

But there is a difference between this sort of borrowing and leverage. There are bad ways to borrow money, but there are also good ways. I’m reminded of the expanding brain meme:

The classic example of using leverage is taking out a mortgage to buy a house. Historically, houses have gone up in value faster than the interest on mortgage payments. This is good.

Let’s say you want to buy a house for $100k. You don’t have all that money outright, so the bank offers to loan you $90k at a rate of 2% a year. You only have to put down $10k of your own money as a deposit, which is a much more manageable amount. You take the deal.

After 1 year, you owe 2% ($1800) in interest to the bank on the $90k borrowed. But the house has increased by 10% in value. That 10% increase is on the entire value of the property (i.e. 10% of $100k) and so you’ve made $10k total profit. Even after you pay the bank its interest, you still have $8200 profit all for yourself – a return of 82%!

The reason it’s an 82% return is because you only invested $10k of your own money. Even though the house only increased in value by 10%, your return is calculated based on the money you invested ($10k). In this example, leverage enables you to get the returns on a $100k asset without actually investing $100k.

It’s worth pointing out that leverage amplifies both gains and losses. But as long as you keep up the repayments on your mortgage, you will never realise the losses. Even if the housing market totally tanks (it won’t – prices are much higher now than before the ‘crash’ of 2007), you’ll at least have somewhere to live. Buying a house is probably a good move if you have no other ideas what to do with your money – especially while interest rates are low.

There are various ways you can utilise leverage beyond property, too – although it can get pretty risky.

With stocks, for example, it can be tempting to increase your holdings on margin. This is when you borrow against the value of your current holdings to buy more. This is great when prices are going up, but if you’re too greedy and prices drop you can get liquidated and lose everything pretty quickly.

One final example of leverage: Returning to the example of borrowing money to buy consumer products like cars and clothes, this is not necessarily bad.

Let’s say you’re going to buy a new car but don’t have the cash to pay for it. You do, however, have assets (stocks, property, etc.) that easily cover the cost of the car. You have two options:

- Sell the assets and buy the car

- Borrow money against those assets and buy the car

Which of these two options is best will depend on interest rates and expected returns. For example, if you can borrow money at 2% a year and you expect the assets to increase 5% this year, it makes sense to borrow/leverage. However, if you can only borrow money at 8%, then it makes more sense to sell the assets and pay for the car that way.

The point with these examples is to illustrate how borrowing – using other people’s money – can either help you escape the wage cage faster or imprison you even more securely within it depending on how you use it.

Wildcards

“Opportunities come infrequently. When it rains gold, put out the bucket, not the thimble.”

– Warren Buffett

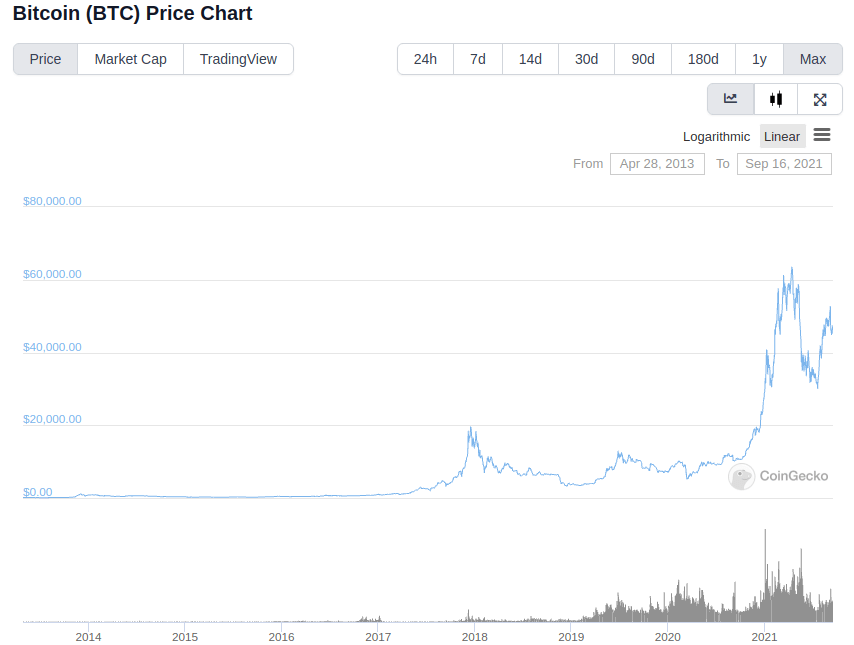

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, wildcards – the rare opportunities where you can 10x, 100x, or even 1000x your money. All it takes is one of these – two, at most – and you’ve escaped the wage cage forever.

The most obvious example of this is Bitcoin. I was first aware of Bitcoin all the way back in 2012 when I was at university, but I didn’t buy any. Even after I started work and became interested in investing, I was too scared to buy Bitcoin. Everyone said it was too risky – what if I lost all my money?

But knowing what I know now, I’d have gone all in on Bitcoin without a second’s hesitation. I’d have taken out all sorts of loans and bought as much as I could. Of course this is obvious to say in hindsight, but even with the information available at the time it was a no-brainer. Sure, I could have lost all my money, but the upside was hugely asymmetric.

And while Bitcoin-tier returns are rare, we’ve had plenty of other crazy bull markets over the decades. For example:

- Property in the 1990s

- Dot com stocks in the 2000s

- Crypto in the 2010s

If you pay attention to the world and keep your ear to the streets, you’ll become aware of these opportunities. And when they present themselves, do not hesitate.

I was way too cautious when I first started investing and trying to make money. I was so scared of losing money that I couldn’t make any. I only invested in index funds and I worried when they dipped 5% or so. I remember procrastinating for ages about spending a few hundred pounds on the first stock for my websites in case I couldn’t sell it.

But you can’t escape the wage cage with this risk-averse mindset. You can maybe retire early if you do the compound interest thing, but even that isn’t guaranteed in this economy. You have to take risks.

The thing that shook me out of this cautious mindset was poker. Through poker, I learned the concept of pot odds, which is a way of calculating a hand’s expected value. Basically, there are situations where you are more likely to lose and yet it still makes sense to play – because the potential wins are asymmetric to the losses.

A simple way to illustrate this is betting on the roll of a 6-sided dice. You’ve got a 1 in 6 chance of getting it right, and a 5 in 6 chance of getting it wrong. You’re more likely to lose.

A simple way to illustrate this is betting on the roll of a 6-sided dice. You’ve got a 1 in 6 chance of getting it right, and a 5 in 6 chance of getting it wrong. You’re more likely to lose.

But if you get 1000x your bet when you win, you should take that bet all day long! For every $5 you lose, you’ll make $1000 profit. Losing is the more common outcome, but the wins more than cover the losses.

I know it’s a basic concept, but understanding pot odds and expected value really shook me out of my risk-averse mindset. And I think it maps fairly neatly on to real life – not just with investments, but starting a business as well. You might lose, but the more you try the more chances you have of hitting a wildcard – and it just takes one wildcard to escape the wage cage forever.

Summary: Escaping the wage cage

- Focus on building wealth and assets over career

- Work on side hustles to build additional income streams and learn new skills

- Don’t borrow money to buy things that depreciate in value, but do use leverage to buy assets that appreciate in value faster than the interest rate of borrowed money

- Keep an eye out for wildcard opportunities with asymmetric upside and take advantage of them when they appear