The 4-Hour Work Week sounds like one of those clickbait articles that fail to deliver. But unlike them, this book won’t leave you disappointed.

I first read The 4-Hour Work Week five or so years ago and reading it again in 2018 I realise what an enormous influence it had on my life. Whether by coincidence of subconscious imitation, I also started an online health supplement company like the author, Tim Ferriss. I’ve automated and outsourced much of the more repetitive stuff and eliminated unproductive tasks. I’m writing this post from Bled, Slovenia, on a sort of mini-retirement of the kind described in the book.

It’s not just me, either. You can find tons of reviews online saying how this book changed the reviewer’s life. The expanded and updated edition I’ve got with me is packed full of testimonies from people who’ve lived up to the book’s subtitle: Escape the 9-5, live anywhere and join the new rich.

So while it is kind of self-helpy in tone, The 4-Hour Work Week is more than just useless platitudes and tired clichés that impart a vague and undirected sense of motivation. It contains practical steps, tricks and examples for how to leverage modern technology (and a 19th century economic principle) to live a more exciting and more productive life.

The New Rich

Written in 2007, The 4-Hour Work Week basically described the ‘digital nomad’ lifestyle before the phrase had even been coined.

But instead of ‘digital nomad’, Ferriss uses the term ‘New Rich’:

“The New Rich (NR) are those who abandon the deferred-life plan and create luxury lifestyles in the present using the currency of the New Rich: time and mobility.”

He tells tales of luxury, travel and adventure – the kind of lifestyle most people say they’d live if money were no object and they didn’t have to work. However, he says, you don’t need to be a millionaire for this to be a reality.

“Here’s the secret I rarely tell: It all cost less than rent in the U.S. If you can free your time and location, your money is automatically worth 3-10 times as much.”

Ferriss’ point is that you don’t necessarily want to be a millionaire, you want to live like one.

On paper, someone earning $200,000 per year is four times richer than someone earning $50,000. But what if the guy earning $50k works just 10 hours per week compared to the $200k guy’s 60 hours? Better yet, what if the guy earning $50k per year from 10 hours a week earns his income entirely independent of location whereas the $200k is tied to an office in an expensive city? Using the “currency of the New Rich” – time and mobility – the ‘lifestyle output’ of the $200k salary is far smaller. The guy earning $50k can live like a millionaire whereas the other can’t.

Ferris’ own story is heavy on the travel stuff. But he’s keen to point out you don’t have to live in another country to benefit from the techniques of The 4-Hour Work Week. You don’t even have to quit your job.

Eliminate pointless tasks

The 4-Hour Work Week is divided into four sections:

- Definition

- Elimination

- Automation

- Liberation

The bulk of the practical advice is contained in the middle two sections: elimination and automation.

Elimination is all about getting rid of tasks that don’t actually matter – getting rid of work for work’s sake (W4W).

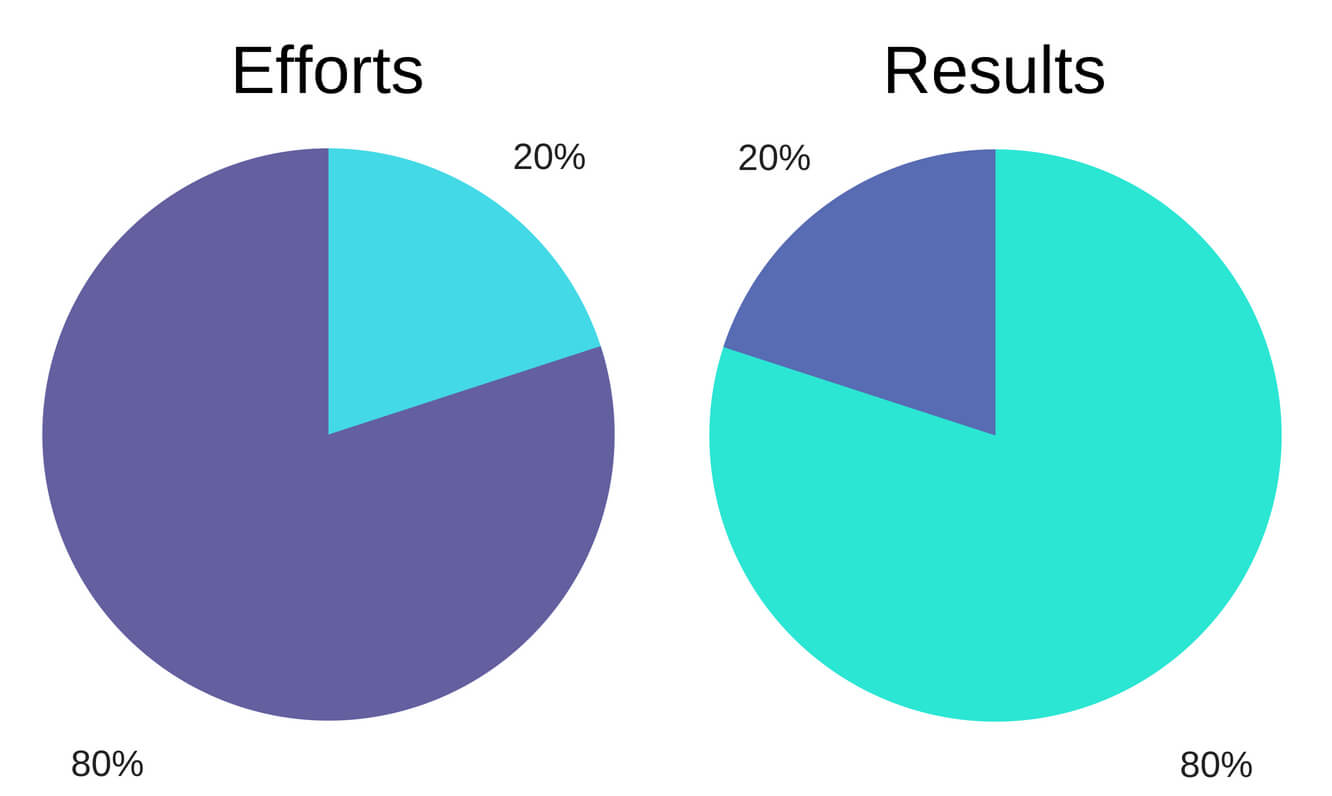

Ferriss talks about the Pareto Principle, often referred to as the 80/20 rule. Vilfredo Pareto, an economist born in 1848, observed that 80% of the wealth and income of society was controlled by 20% of the population. But, he realised, these distributions could be found everywhere and in all sorts of surprising places. For example, 20% of Pareto’s pea pods in his garden produced 80% of the peas.

There are tons of examples of these skewed distributions. For example, in most companies, 80% of profits often come from 20% of the products and 20% of the customers. 80% of stock market profits come from 20% of the portfolios of 20% of the investors.

The most relevant example here is that 80% of results often come from 20% of efforts.

How much of your work time is spent in useless meetings? Or idly checking emails? How much of your workload consists of pointlessly pushing papers? Come on, be honest!

The aim, then, is to identify the 20% of effective tasks that generate 80% of the results and eliminate the rest.

This productivity hack is further amplified by leveraging Parkinson’s Law: the observation that people tend to take exactly the amount of time they’re given to complete a task. Setting short deadlines for the 20% of productive tasks forces you to focus on only the important steps.

After strictly applying these techniques, Ferriss says:

“I went from chasing and appeasing 120 customers to simply receiving large orders from 8 […] My monthly income increased from $30K to $60K in four weeks and my weekly hours immediately dropped from over 80 to approximately 15.”

He distinguishes being effective from being efficient. Efficiency is about performing a task in the most economic manner regardless of whether or not that task is important. Being effective is defined as “doing the things that get you closer to your goals”.

Successful elimination is all about being effective rather than efficient.

Automate or outsource the remaining simple tasks

Once you have eliminated time-wasting tasks and stripped your efforts down to those that are truly productive, the next stage is to automate/outsource them.

Ferriss describes utilising a fulfilment service to distribute his health supplements. He also hired a virtual assistant based in India (for $4-10 per hour) to handle simple but time consuming tasks. This freed up a huge amount of time and effort, allowing him to focus on only the important stuff (or go skydiving or salsa dancing or whatever).

The automation section is so relevant today that it’s easy to forget this book was written in 2007. Ferriss indirectly predicted the rise of freelancing sites like Upwork and Fiverr before they even existed. He explained the dropshipping business model – where you generate orders for a company that fulfils them – before it became popular.

“This creates a curious business phenomenon: Negative cash flow is impossible.”

That said, it’s much harder to make successful use of these methods in 2018 than it was back in 2007. Everyone knows about them now and it’s insanely competitive. Services like Shopify and Oberlo mean you don’t even need to know HTML to set up a store stocked with thousands of products – all in a matter of hours and for less than $1000.

But Ferriss’ discussion of automation and outsourcing has applications far broader than just dropshipping health supplements from a beach in Thailand. What I really like is how he challenges the reader to think entrepreneurially – even as an employee.

Jean-Baptiste Say, the French economist who coined the term ‘entrepreneur’, defines his term:

“The entrepreneur shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield.”

And this is exactly what Ferriss draws out. He encourages the reader to seek out all sorts of arbitrage opportunities where resources – whether they be time or money – can be moved from areas of low productivity to high productivity.

The obvious example of this is taking advantage of currency differences. If you’re earning money in US Dollars and spending it in Thailand Baht, say, the lifestyle output of each dollar you earn will be far greater. But arbitrage opportunities can also be found domestically and within the scope of paid employment.

“If you spend your time, worth $20-25 per hour, doing something that someone else will do for $10 per hour, it’s simply a poor use of resources.”

An alternative blueprint for millennials

When you’re younger you get sold a generic blueprint for success: study hard in school, go to college and get a good job when you graduate.

But the reality is this outcome is far from guaranteed – especially in today’s economy.

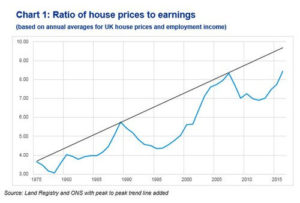

This ‘boomer blueprint’ worked well four or five decades ago. The economy was growing and so were wages. College tuition was a fraction of the price it is today and upon graduation you could comfortably afford a mortgage for a decent sized house – a leveraged asset that would greatly increase in value throughout your working life and allow you to retire comfortably – on an average salary.

For college graduates today this blueprint is broken.

Wages haven’t increased since the turn of the century while inflation has marched on – especially when it comes to accommodation. Instead of building up equity in an appreciating asset – a house – and accumulating wealth, millennials are handing over a far greater portion of their stagnant incomes (in the form of rent) to the generation that sold them this broken blueprint.

Wages haven’t increased since the turn of the century while inflation has marched on – especially when it comes to accommodation. Instead of building up equity in an appreciating asset – a house – and accumulating wealth, millennials are handing over a far greater portion of their stagnant incomes (in the form of rent) to the generation that sold them this broken blueprint.

But it’s not all bad news. You just need a different blueprint. And this is what The 4-Hour Work Week provides.

“If everyone is defining a problem or solving it one way and the results are subpar, this is time to ask, What if I did the opposite? Don’t follow a model that doesn’t work. If the recipe sucks, it doesn’t matter how good a cook you are.”

Technology has made it cheaper and easier than ever to start a business. Whereas previous generations would have to risk enormous amounts of capital on premises, stock, advertising, etc., these start-up costs have virtually disappeared thanks to the internet. An online store today needs no physical address. Dropshipping arrangements remove the up-front cost of stock. Social media and organic search have made it possible to reach huge audiences for free.

What’s more, the internet has opened up the possibility of geoarbitrage like never before. How could you have hired a virtual assistant or outsourced work to someone in another country before the internet? Can you imagine, back in 1970, trying to convince your boss to let you work remotely while you went travelling round the world?

So, while changes in the economy have made it more difficult for millennials in some ways, other changes make it much easier.

A decade on from the book’s publication, the rise of freelancing, the gig economy and new terms like ‘digital nomad’ suggest that, whether by choice or necessity, the old career blueprint is being replaced. The 4-Hour Work Week draws on these changes in the economy – technology, globalisation, automation – and shows how to make them to work for you.

The contrarian life hacker’s Bible

“Different is better when it is more effective or more fun.”

The 4-Hour Work Week sounds like a book about how to be lazy, but it isn’t. It’s a book about how to make more effective use of your time.

The contrarian spirit reminds me a lot of Zero to One and is a big reason why I love this book so much. Both Zero to One and The 4-Hour Work Week emphasise the importance of doing things differently. However, it’s not about doing things differently just for the sake of being different, it’s about finding ways to do things better.

It all sounds crazy at first. But the more you buy into Ferriss’ mindset the more you realise it’s the status quo that’s crazy rather than the other way round.

- If you can get a week’s work done in four hours, why sit around for eight+ hours a day pretending to be busy?

- If technology means you can get the same work done from home (or a beach in Thailand), why do you have to go into an office five days a week?

- Why get stressed out by the 80% of tasks that don’t produce results?

- Why dedicate the majority of your waking life to something you don’t enjoy or care about?

The book’s title sounds too good to be true: “live anywhere and join the new rich” from a “4-hour work week”.

“Much of what I recommend will seem impossible and even offensive to basic common sense – I expect that. Resolve now to test the concepts as an exercise in lateral thinking. If you try it, you’ll see how deep the rabbit hole goes, and you won’t ever go back.”

And while it’s not easy, The 4-Hour Work Week shows it is at least possible. The cult following this book has garnered along with its many success stories is testament to this.

But even if you fall short of this ambitious target, The 4-Hour Work Week opens your mind to different – and better – ways of doing things.