Contrarian investors believe that human psychology leads to market inefficiencies that create investment opportunities.

It’s still a matter of debate whether such inefficiencies exist, how often they occur, and to what extent. If there was a way of consistently identifying such inefficiencies, whoever could do so would probably become the richest person on the planet.

But it seems clear to me that there is a psychological component to investing. There are biases that cause investors to make bad decisions and, more importantly, there are personality traits that seem to help investors beat the market. Below are some of my thoughts on the psychology of contrarian investing and contrarian thinking in general.

Social pressure and authority

We typically think of ourselves as rational free thinkers – that we don’t believe things simply because we’re told to, or that we wouldn’t believe something just because that’s what everyone else believes.

But psychological experiments repeatedly demonstrate this isn’t the case. Of particular interest in the context of contrarian investing is the influence of crowds and the influence of authority.

The Asch conformity experiments are a good example of how humans are biased towards group consensus. In these tests, a group of eight people were given the simple task of saying which of the three lines opposite – A, B, and C – was closest in length to the other line. However, only one of these people was an actual test subject – the rest were actors.

The actors would all say an obviously wrong answer. And by the time the test subject had to give their own answer, Asch found that a large percentage of subjects (36.8%) would give the same, incorrect, answer so as to conform to the group.

“The subject denies the evidence of his own eyes and yields to group influence.”

Another study with similar findings is the smoke-filled room experiment. In this test, subjects were asked to complete a short written survey. However, as the subjects were completing the survey, smoke would start billowing into the room from outside.

In scenario 1, the subjects would complete the survey alone in the room. When alone like this, subjects would soon get up to investigate the smoke and go outside to alert someone of the potential danger.

But in scenario 2, subjects would complete the survey with other people – actors – in the room. The actors would all ignore the smoke and act like nothing was happening. In this group scenario:

“only one of the ten subjects… reported the smoke. the other nine subjects stayed in the waiting room for the full six minutes while it continued to fill up with smoke, doggedly working on their questionnaires and waving the fumes away from their faces. They coughed, rubbed their eyes, and opened the window – but they did not report the smoke.”

It’s clear that humans are highly susceptible to group pressure, conformity, and the madness of crowds. And this influences their investment decisions.

But in addition to social pressure, it’s also worth mentioning our bias towards the opinions of authorities. The Milgram experiments, where subjects were prepared to administer a lethal electric shock to another person simply because an authority figure told them to, are the most well-known demonstrations of authority bias.

And authority figures – such as governments, mainstream media, ‘prestigious’ institutions, and respected individuals – move markets. A single comment from a famous investor or a damning editorial in a newspaper can significantly sway people’s investment decisions. The same instincts also make investors biased towards credentials and political correctness.

Contrarian investing is about overcoming these psychological biases. The crowd or the authority figure may be correct – but this is far from guaranteed.

Contrarian investing

The naive way to think of contrarian investing would be something like:

“When everybody thinks alike, everybody is likely to be wrong.”

– Humphrey B. Neill, The Art of Contrary Thinking

And while this sounds good, it’s a claim that probably isn’t supported by the data. If your investment strategy is to simply do the opposite of what everyone else does, you’ll probably be worse off than if you just go with the majority.

Instead, contrarian investing is about overcoming the biases towards authorities and groupthink in your valuations. It doesn’t matter that “most people think x” or that “this respected institution says y”. All that matters is their reasons. All that matters are the underlying facts. And often, such fundamental reasons are lacking.

To simply do the opposite of what the crowd does is to put too much faith in the crowd’s ability to assess the facts. It’s not that each member of the crowd makes a rational assessment of the facts and then does the opposite – it’s that the crowd often neglects to assess the facts at all. Just like in the Asch conformity experiments or the Milgram experiments, people’s investment decisions get distorted by psychological biases and become decoupled from the underlying facts.

And so a better characterisation of the contrarian mindset comes from Peter Thiel in one of my favourite books, Zero to One:

“That doesn’t mean the opposite ideas are automatically true: you can’t escape the madness of crowds by dogmatically rejecting them… The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.”

Imagine this: You’re researching some pharmaceutical company with tons of valuable patents, new drugs nearing regulatory approval, and the company is profitable. However, its price-earnings ratio is only 3. If you saw that, you might think: “if the company is that good then why is the price so low?”

A more likely scenario is the reverse: You keep hearing about this fashionable new Silicon Valley startup that’s going to change the world. However, it’s currently losing millions of dollars every month and would need to grow by an absurd multiple to ever become profitable. People are flocking to invest money in this company, giving it some huge valuation. You think: “there must be something about this company I’m missing otherwise all these people wouldn’t be investing in it.”

In both these cases you’re looking to the price as a guide to the value of a company.

But to do this is to defer thinking to the group rather than thinking for yourself. And when everyone does this, bubbles form. Yes, maybe there is something the market knows that you don’t – but the price itself doesn’t guarantee this.

Warren Buffett

When I hear the name Warren Buffett, I don’t immediately think of someone who takes particularly bold contrarian stances. His investments – at least in recent years – always seem pretty mundane: food and drink, insurance companies, farms. He loves talking about farms.

But Buffett is the originator of what is probably the most famous quote on contrarian investing:

“be fearful when others are greedy and greedy only when others are fearful”

– 2004 letter to Berkshire Hathaway investors

In isolation, this quote seems to advocate simply doing the opposite of what everyone else is doing. But it’s not that easy. To just do the opposite of what everyone else does is not truly contrarian for the reasons described above.

Instead, Warren Buffett’s approach – value investing – is, once again, about thinking for yourself.

“You need a temperament that neither derives great pleasure from being with the crowd or against the crowd, because this is not a business where you take polls – it’s a business where you think. And Ben Graham would say that you’re not right or wrong because 1000 people agree with you, and you’re not right or wrong because 1000 people disagree with you. You’re right because your facts and your reasoning are right.”

With value investing, you make your own assessment of the stock’s value through some sort of fundamental analysis. You consider only the relevant underlying facts – not the opinions of analysts or the sentiment of the crowd.

And you can see in the interview above how conscious Buffett is of being swayed by such influences. He chooses to remain in Omaha rather than move to Wall Street because this means he is insulated from the “whispering” of other people in the industry. He also says he’d rather not know the current stock price until after he’s made his assessment of the value of a business.

Anyway, once the contrarian investor has made their valuation, Buffett would say they have the opportunity to deal with Mr. Market. Mr. Market is an allegory for the current market price for a stock, and was originally described by Ben Graham.

Unlike the contrarian investor, Mr. Market is prone to psychological biases. Depending on his mood that day, Mr. Market will quote you a different price to buy a business. If Mr. Market is depressed, say, he’ll offer you a price much lower than what your fundamental analysis says the business is actually worth. When this is the case, you buy. After all, Mr. Market’s emotions don’t tell you anything about the actual value of the business.

It all sounds so easy – too easy, in fact. You’d think by now clever people would recognise these arbitrary moodswings and become less irrational. You’d at least expect financial institutions – with all their data and money and time to spend analysing fundamentals – not to be so careless.

But to expect that would again be to put too much faith in crowds and authorities.

The Big Short

I love this film. It’s the perfect contrarian tale. And it’s based on the very real story of the 2008 financial crisis.

The Big Short illustrates the negative consequences both of putting too much faith in the crowd and of putting too much faith in authority. It also illustrates how “outsiders and weirdos” – aka contrarian investors – can benefit from such situations.

“A few outsiders and weirdos saw what no one else could… These outsiders saw the giant lie at the heart of the economy and they saw it by doing something the rest of the suckers never thought to do: They looked.”

One of the first scenes in the film sees hedge fund manager Michael Burry asking an employee to analyse the individual loans that make up various mortgage bonds. Given the amount of money invested in these bonds, you would expect that a million other analysts had done this already. You would expect someone else to have raised the alarm if these bonds were anything less than watertight. But that’s the problem: everyone just assumes everyone else is checking this stuff, and so no one ends up checking it for themselves. In reality, most people dealing with these bonds had deferred their valuation of them to the crowd rather than thinking for themselves.

Michael Burry analysed these bonds for himself, saw that the crowd were wrong, and made a big profit when he turned out to be right. I bet if Burry was a subject in one of Asch’s experiments, he would have no hesitation to go against the group and give the correct answer.

Then there’s authority figures and institutions.

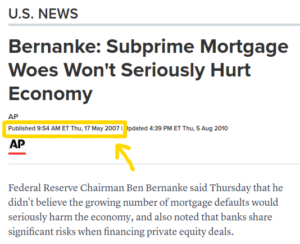

If you can’t count on the crowd to accurately value these bonds, surely prestigious authorities such as the Federal Reserve and objective institutions such as Standard and Poor’s and Moody’s can be trusted. After all, it’s their job to know this stuff.

But again, no. The encounter between FrontPoint Partners and Standard and Poor’s demonstrates how such institutions are not necessarily incentivised to be the impartial and objective authorities they are held up as:

“If we don’t give them the ratings, they’ll go to Moody’s – right down the block. If we don’t work with them, they will go to our competitors. It’s not our fault. It’s simply the way the world works.”

FrontPoint Partners decided to go against the authority of these institutions. Like Michael Burry, they thought for themselves and ended up beating the market.

Can you consistently beat the market?

When I first started learning about investing, I bought into the whole efficient market hypothesis. I read books like A Random Walk Down Wall Street (which I still think is a great book) and became convinced that it was highly difficult – if not impossible – to beat the market.

But now I’m not so convinced. Humans are irrational by nature and there is reasonable empirical evidence against the efficient market hypothesis1,2. Plus, there are just so many anecdotal examples of market irrationality.

Perhaps increased computerisation and algorithmic trading can make markets more rational – but this didn’t prevent the 2008 housing bubble. And just off the top of my head I can recall several examples of overvalued investments in the age of big data and algorithms:

- WeWork

- Juicero

- Theranos

- Uber

- About a million crypto scams

Given this, my own belief is that it is possible for contrarians to beat the market. And I also believe that certain psychological characteristics are conducive to doing so.

The psychology of contrarian investing

Casual observation of the kinds of stories above suggests that successful contrarian investors often share common features. It’s purely anecdotal, of course, but if I were to profile the contrarian investor in the language of the five factor personality model, I would expect them to be something like:

- Low agreeableness

- Low neuroticism

- Low extraversion

- High openness

- High conscientiousness

The first two, in particular, seem important psychological traits for contrarian investors. Being contrarian pretty much requires you to be at least somewhat disagreeable. If you put too much trust in others or are too compliant (traits typical of agreeable people) then it will be difficult to go against the crowd and against convention. And secondly, as Warren Buffett mentions in the interview above, you need a stable personality and temperament – in other words, low neuroticism. This makes sense as being emotionally stable will likely prevent you from FOMO buying or panic selling in response to price movements.

One other observation I have noticed in the context of contrarian investing (and contrarian thinking in general) is a link to autism spectrum disorders.

Again, the evidence is anecdotal, but there are plenty of examples of contrarian investors with autism spectrum disorders. Michael Burry – the contrarian hedge fund manager described above – has self-diagnosed himself as having Asperger’s, for example. And last year, Institutional Investor published an article about money managers on the autism spectrum, with one commenting:

“The movement toward more quantitatively rigorous and more well-defined portfolio management practices, more quantitative investing, is definitely a huge trend… It’s definitely more of a benefit toward people that are on the autism spectrum than not.”

It makes sense that autism could be an advantage for the contrarian investor. A key symptom of autism spectrum disorders is social impairment. And while this social impairment has its disadvantages, it seems plausible that a reduced sensitivity to social norms may make autistic individuals less prone to the kinds of biases described earlier – particularly those related to groupthink and conformity.

Peter Thiel makes a similar case in Zero to One, arguing that autism spectrum disorders such as Asperger’s may be an advantage in business more broadly:

“The hazards of imitative competition may partially explain why individuals with an Asperger’s-like social ineptitude seem to be at an advantage in Silicon Valley today. If you’re less sensitive to social cues, you’re less likely to do the same things as everyone else around you. If you’re interested in making things or programming computers, you’ll be less afraid to pursue those activities single-mindedly and thereby become incredibly good at them. Then when you apply your skills, you’re a little less likely than others to give up on your own convictions.”

One other psychological trait that may benefit the contrarian investor is optimism.

Taking the contrarian position is often likely to mean being bearish. But given that markets generally trend up over the long term, being constantly bearish is unlikely to be profitable in the long run.

Further, being overly bearish can still mean losing money even when you’re right. As John Maynard Keynes famously said:

“Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

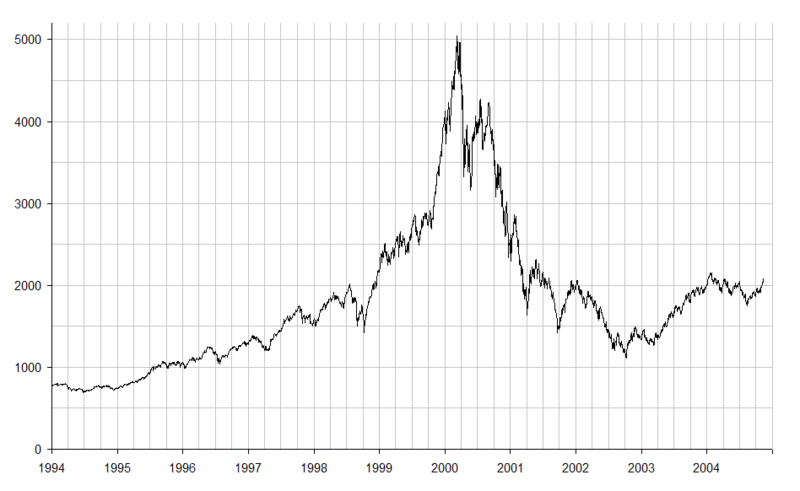

And this lesson is again illustrated in The Big Short. Despite being fundamentally correct, the various characters in the film initially lose money as the bubble they’ve bet against continues to inflate. If the market remained irrational for longer, The Big Short would be a very different story.

Another example that springs to mind is Bill Ackman’s bet against Herbalife, as covered in the excellent documentary Betting on Zero.

At least as it’s presented in the documentary, Herbalife is pretty clearly a pyramid scheme. Given this, Ackman takes a huge short position in Herbalife, expecting regulators to act and the company to collapse. But Herbalife stock continued to rise, and in February 2018 Ackman closed his position at a massive loss.

If you’re correct on a bearish valuation but wrong on timing, it’s ultimately the same thing as being wrong. High collateral costs can reduce or even completely wipe out your returns. But if you make a bullish valuation and have to wait, the only cost is the opportunity cost of other investments as you wait for the market to catch up to you.

Perhaps this is why Warren Buffett is such a consistently successful contrarian. In a recent interview with CNBC, he mentions that he’s been a net buyer of stocks every year. Buffett’s contrarian approach is an optimistic one – he seeks out undervalued companies rather than betting against overvalued ones.

Beyond investing

It’s simply not practical to research and think through every single issue. And most of the time, looking to the crowd or authority figures is a useful shortcut for arriving at the truth.

But that’s all these biases are: A shortcut.

If you’re making an important decision, don’t operate under the assumption that everyone is competent and knows what they’re doing – because they often don’t. It’s not just finance, either. Biases towards authority figures and peer pressure are human nature and distort fields such as science, politics, and culture too.

Worrying as this may be, the good news is that human irrationality creates huge opportunities – not just for investing.

If you are able to think things through for yourself without bias, you can discover new truths and better ways of doing things. The mainstream might oppose you initially, but if you maintain courage in your convictions and stay positive, you will be rewarded – as long as you are fundamentally correct.