“What important truth do very few people agree with you on?”

Most business books offer the same generic advice. But Zero to One is different.

And that’s kind of the biggest theme throughout the book. Despite covering a huge range of topics – economics, society, politics, investment, entrepreneurship – there is a constant emphasis on thinking for yourself instead of simply going with the conventional wisdom.

In other words, doing something different.

Peter Thiel is a venture capitalist, co-founder of Paypal and was the first outside investor in Facebook. Zero to One is based on notes from a course he taught at Stanford University back in 2012. Thiel has gained a reputation as something of a contrarian in Silicon Valley – and this definitely comes across in the book.

But the message of Zero to One is not that we should disagree with convention for the sake of being different. It’s more that we shouldn’t use conventional opinion as a shorthand for arriving at the truth.

If you think for yourself and arrive at a contrarian conclusion that’s also true, he says, then this might be the foundation for a successful business or a way to radically improve the world.

Horizontal vs. vertical progress

“If you take one typewriter and build 100, you have made horizontal progress. If you have a typewriter and build a word processor, you have made vertical progress.”

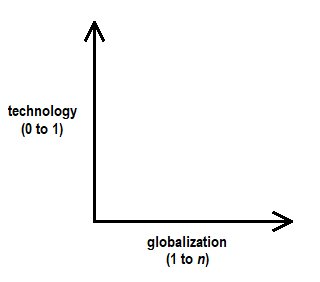

Horizontal progress means going from one to n – doing more of the same.

But you can also make vertical progress by doing new things. This is what Thiel means by going from zero to one.

The effects of going from zero to one extend beyond its impact at the level of the entrepreneur, though. There are also significant macroeconomic implications.

Thiel describes two main modes of macroeconomic progress throughout history: globalization and technology.

Thiel describes two main modes of macroeconomic progress throughout history: globalization and technology.

Globalization has brought with it huge economic benefits. Free trade and the global exchange of ideas and capital have made many people better off. Thiel categorizes this as horizontal progress.

But, he argues, we can’t rely on this horizontal progress as an indefinite source of economic growth. If every one of India’s millions of households were to live the same way we currently do in the USA and Europe, for example, the result would be environmentally catastrophic. Similarly, if China’s energy production were to double without new ways of generating energy, then emissions would also double.

Thiel’s first contrarian opinion is that globalization will be far less important for the future than vertical progress – i.e. technology – will be.

New technology

“We wanted flying cars, instead we got 140 characters.”

When you hear the word ‘technology’, your first thoughts are likely to be of computers, mobile phones, the internet and so on.

But this is just one type of technology: information technology.

Thiel says this wasn’t always the case. The first half of the twentieth century saw technological progress in a wide range of areas: the Apollo program sent space shuttles to the moon, Penicillin made life-threatening infections simple to cure, mass production of cars and advances in aviation made travel quicker and more affordable.

But over the last few decades progress in these areas appears to have stalled.

In fact, Thiel argues, the rate of progress has actually reversed in many cases. The number of new drugs approved by the FDA per billion dollars has halved every nine years since 1950. The supersonic jet Concorde has been decommissioned and security checks at airports mean it often takes longer to get where we’re going. We haven’t been back to the moon since 1972.

This brings us to another contrarian view. It’s common for experts to cite Moore’s Law as an example that technological progress is accelerating. But Thiel says the very opposite – at least in his broader definition of the word technology.

“The smartphones that distract us from our surroundings also distract us from the fact that our surroundings are strangely old: only computers and communications have improved dramatically since midcentury.”

He cautiously speculates as to why this might be. For example, he talks about indeterminate and determinate optimism and pessimism as well as a general cultural malaise. His discussion of increased government regulation as a possible factor – especially in areas outside of computers – rings true with my libertarian instincts. But it’s impossible to answer these why questions definitively, as Thiel himself notes.

Either way, there may be low-hanging fruit in these neglected areas of technology. The fact that there has been less progress in these areas is not necessarily an indication that it’s harder to innovate in them.

The monopoly argument

“Monopoly is therefore not a pathology or an exception. Monopoly is the condition of every successful business.”

This is arguably the most famous (and misunderstood) contrarian claim in Zero to One: that monopolies are a good thing and something every business should strive toward.

But Thiel’s idea of a monopoly is very different to what economists typically think of.

Here, monopolies are not mere rent collectors who’ve cornered the market in some unfair way. Instead, they’ve earned their monopoly status:

“by “monopoly,” we mean the kind of company that’s so good at what it does that no other firm can offer a close substitute.”

A good example of this kind of monopoly – and one that Thiel uses – is Google.

Google’s search algorithm is so good that it’s managed to achieve more than 80% market share in the UK (slightly less in the USA). It’s so ubiquitous that the very word – ‘Google’ – has made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary as a verb.

Google’s dominance is so strong, Thiel says, that it has to tell lies to avoid being called a monopoly.

Rather than describing itself as a search engine, a market in which it effectively has a monopoly, Google will say it’s competing in much larger markets. It might say it’s competing in online advertising, or advertising in general.

Google could even call itself a tech company in which case it’s competing with the likes of Apple and Microsoft. Chrome, Android OS, self-driving cars, etc. can all be pointed to as evidence that Google faces fierce competition despite the fact that almost all the revenue comes from its search monopoly.

The opposite of a monopoly is a perfectly competitive business.

Like monopolies, competitive businesses also tell lies – but in the other direction. Whereas monopolies downplay their dominance, competitive businesses exaggerate how unique they are.

Like monopolies, competitive businesses also tell lies – but in the other direction. Whereas monopolies downplay their dominance, competitive businesses exaggerate how unique they are.

A British food restaurant in Palo Alto could call itself the only one in its industry. But is this the best way to think about it? Or is the more accurate way to describe it ‘just another restaurant’?

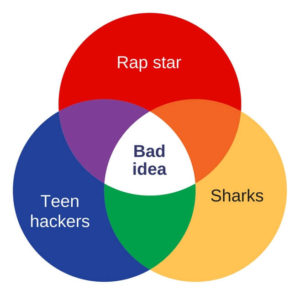

It’s a similar story in creative pursuits. Imagine a movie about a rap star who joins an elite group of hackers to catch the shark who killed his best friend. It’s certainly the only one in its category, but it’s not a monopoly.

Google’s monopoly, in contrast, is both unique and valuable. It’s earned its position by providing immense value in a way that the competition doesn’t and can’t.

So, in contrast to the negatives we typically associate with them, monopolies are actually a good thing – both for the customer and the business owner.

“Even the government knows this: that’s why one of its departments works hard to create monopolies (by granting patents to new inventions) even though another part hunts them down (by prosecuting antitrust cases).”

We shouldn’t worry about monopoly restricting innovation, either. In fact, Thiel argues the very opposite.

Monopoly profits provide powerful incentives for the kind of innovation that improves the world. IBM enjoyed immense profits throughout the ’60s and ’70s thanks to its hardware monopoly. This was then superseded by Microsoft’s software monopoly in the ’90s. Now, the landscape is changing once again thanks to a growing preference for mobile devices.

Rather than restricting choice, zero to one monopolies like Google give customers new choices by creating entirely new industries.

This takes us to perhaps the most important of Thiel’s contrarian views:

“Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away.”

We tend to think of capitalism as synonymous with competition. But with nothing else to differentiate them, businesses compete to undercut each other on prices. This race to the bottom is unsustainable and ends with companies sustaining losses, losing capital and eventually going out of business.

Good capitalism, Thiel argues, is about distinguishing yourself such that you don’t have to compete like this – by going from zero to one.

Psychological observations

“The most contrarian thing of all is not to oppose the crowd but to think for yourself.”

Littered throughout the book are insights into the psychology of innovation. It’s these observations I found to be the most interesting.

Thiel uses his early career experience as an example of what not to do.

He describes a successful, but ultimately very tracked and uncreative, educational experience. After graduating from Stanford with an undergraduate degree in philosophy, he went on to gain his J.D. from Stanford law school. He describes an intensely competitive tournament-like environment and the disappointment that came with failing to win a Supreme Court clerkship upon graduation.

In hindsight, though, this was probably a good thing. If he’d succeeded at this final stage of the tournament he likely would never have started Paypal.

And ‘tournament’ is a word Thiel often uses to describe higher education and the prestigious careers that follow. He talks about our obsession with competition for its own sake and how this can lead us to lose sight of the bigger picture.

This in particular struck a chord with me. After graduating, I didn’t give any serious thought to what I wanted to do. I knew there were certain ‘good’ careers and I wanted one without asking why.

But these prestigious careers are intensely competitive, difficult, boring, and often don’t pay enough to make it worthwhile. The fact that everyone wants to do them creates an oversupply of employees, leading to job insecurity that employers use to their advantage. You may find yourself working extra hours and getting swept up in vicious office politics just to get ahead in the tournament of competition. Returning to the monopoly idea above, it’s the career equivalent of starting a restaurant in Palo Alto.

From an outside perspective, it can be difficult to understand what drives people to do this to themselves.

I’ve seen Peter Thiel give interviews where he says he’d probably still go to Stanford if he had to do it all again – but he’d ask a lot more questions. In a career sense, mine would be:

- Do I enjoy this?

- Am I playing to my strengths?

- Am I genuinely creating value?

- Is this meaningful?

Thiel then goes on to speculate that this mindless competitive instinct may explain a peculiar phenomenon in Silicon Valley: “why individuals with an Asperger’s-like social ineptitude seem to be at an advantage”.

I’m sure we can all think of examples of this. The tech-nerd-genius-billionaire is an archetype for a reason. Thiel suggests that being less sensitive to social cues means these individuals are less likely to buy into competition for the sake of competition and more likely to think for themselves. They pursue their interests single-mindedly and become highly proficient at them – not for prestige or to impress others, but because they genuinely care what it is they’re doing.

There are a load more insightful psychological musings throughout the book, such as the innovator’s attitude to luck. Thiel covers many of these themes in his talk at SXSW from 2013:

Zero to One

“But while I have noticed many patterns, and I relate them here, this book offers no formula for success.”

If this summary seems to jump from topic to topic that’s because my enduring impression of the book is like that.

Zero to One covers a huge range of subjects – many more than I’ve discussed here – despite being relatively short. Its scope is broad but there is an internal consistency throughout the diverse range of topics that demonstrates Thiel’s powerful intellect and capacity for deep and original thought.

However, if you’re looking for a practical guide on how to start a business, Zero to One is not it.

As Thiel himself emphasizes, there is no formula for innovation. And if there was, everyone would follow it and it would no longer work.

That’s the whole point, though. Zero to One challenges readers to think for themselves. It asks difficult questions such as “what important truth do very few people agree with you on?” instead of repeating the same old anecdotes and clichés.

Zero to One is a book I highly recommend everyone to read regardless of whether or not you’re looking to start a business. You might not agree with all of it, but it’s guaranteed to make you think.